Nick Vaughan and Jake Margolin at Devin Borden, Houston.

What’s the difference between prejudice and fantasy? Texas incarnates a big chunk of the American dream, notably in relation to a specific landscape, the one of the Wild West, with its reddish canyons and strategically designed myths of autochthon tribes fighting heroic cowboys whitewashed as straight and Caucasian. On this image is superimposed others of oil derrick pumping endlessly in arid plains and deep-sea waters, as well as skyscrapers drawn from what seems a Yankee version of Dubai. But the reality of the third largest art market of the USA is of course something else: a wide range of climates gives to its eastern part a pleasantly temperate, although a bit humid, landscape with big trees, rivers, and national parks. If the state is very conservative on many points, notably in regard to social issues like women’s rights and immigration policies, it also hosts an excellent network of public schools and leading universities, hosting science and humanities departments that conduct cutting edge research programs entrusted with ideological pressure from generous sponsoring from patrons eager to push forward the thriving economy of their state.

American Dirt. Found photographs by Jeff Ferrell. Organized by Gavin Morrison and Fraser Stables/Atopia Projects at the Reading Room, Dallas.

For few years now the push to feature more content about Texas has prevailed in Mexico City, driven by a sense of necessity, timing, and crucial personal intuition. For if the two neighbors share the history of a fluctuating border that has repeatedly excited tensions during the last centuries, especially for the daily life and politics of inhabitants of border towns such as Laredo, Brownsville or El Paso, the cultural aspect of the relationship remains a myth. If the north of Mexico definitely acknowledges being influenced by US culture, the contrary isn’t always true for Texas, where many people of Mexican origins disregard this aspect of their genealogy. At the same time, a lot of younger American people of Mexican descent come to Mexico City in search of their roots, notably linguistic. Visiting Texas definitely leads to a finer understanding of both cultures, breaking away from clichés to access finer approaches of identity and territory-related notions applied to art, theory and cultural production.

Pedro Reyes and Terence Gower at Labor, Mexico City. Dallas Art Fair 2016.

Texas, in the lineage of its universities, which themselves host interesting contemporary art programs (like the Blaffer in Houston or the Blanton in Austin) host a great deal of strong institutions. The Menil Collection in Houston is an almost century-old collection rooted in a deep understanding of modern vanguards as seen from the upper class US provincial codes. In a humanistic attempt, the Menil gathered in their collection as much occidental art from their immediate artistic entourage as masterpieces from ancient, non-occidental cultures. The Menil also bought the houses in the immediate vicinity of the collection in order to offer affordable housing to the artistic community of the city, lastingly positioning Houston as the hospitable place for artists, a position recently challenged by thriving hip neighbor Austin. Around that legacy first gravitates the Museum of Fine Arts, whose program has been pioneering, for instance, in Latin American art (Gabriela Rangel now director of the Americas Society in NY used to work there). The collection-less Contemporary Art Museum is an agile institution whose curator Dean Daderko is not afraid of feminists, people of color, and queer heroines such as recently Joan Jonas, Gina Pane, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Wu Tsang or MPA: a bold program interestingly supported by the local board. Local galleries embrace the mission of unveiling local talents, such as lately Anthony Sonnenberg at Art Palace, Rodrigo Valenzuela at David Shelton, and Nick Vaughan and Jake Margolin at Devin Borden, with a remarkable project about LGBT life during the American Frontier era entitled 50 States. Sicardi Gallery establishes since the 90s a quite successful intra-Americas dialogue among local collectors and institutions. Visited to know more about late Pop Mexican-American artist Luis Jimenez, Gallerist Betty Moody –who opened her space in the 60s– confessed to me that, “Texas artists had never formed any formal movements because they were too individualist”.

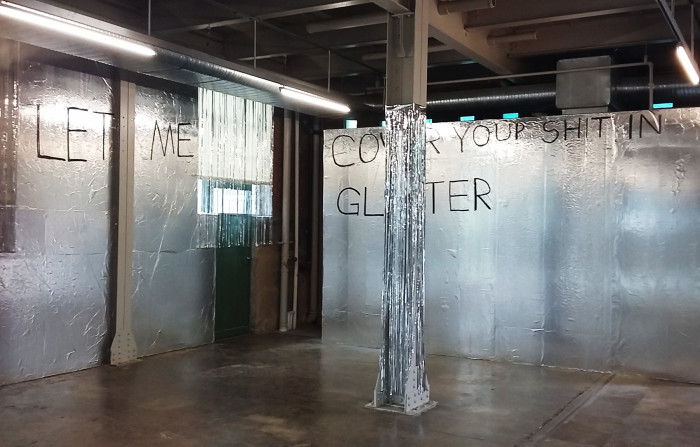

Karl Holmqvist at the Power Station, Dallas. April 2016.

To name a few interesting works I saw during the Dallas Art Fair opening include: Yamini Nayar at Wendi Norris, San Francisco; TR Ericsson at Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels; Lauren Woods at Conduit Gallery, Dallas; Gelitin at Massimo de Carlo, Milano; Trevor Shimizu at Misako & Rosen; Ida Ekblad at Karma International, Zürich/Los Angeles; Naama Tsabar at Páramo, Guadalajara; John Dilg at Jeff Bailey Gallery, Hudson, NY; Terence Gower at Labor, Mexico City, among others.

Lauren Woods, video still from Tempest Tossed Variations 1 & 2 // Courtesy of Zhulong Gallery.

In town, Rebecca Warren at the Dallas Museum of Art and Mai Thu Perret at the Nasher Sculpture Center offered meditative visits over both distinct, femininely engaged sculptural practices. In the Fair Park neighborhood, Karl Homlqvist presented a successful installation at the Power Station, a great not-for-profit, privately run initiative that I have admired from the Internet for quite a while. Nearby is located CentralTrak, a residency program of University of Texas hosting artists studios and an exhibition space –where a quite intriguing painting show by Angelika J.Trojnarski is up currently. The tiny Reading Room led by facetious Karen Weiner, is also worth the visit. It’s a space interested in the links between contemporary art, literature and concrete poetry, and where transparent vinyls by Kenneth Goldsmith adorn the shelves and Scottish curators do shows about found material garbage –the show reminded me of my first artworks as much as it celebrated the past richness of a life unspent on Instagram. The Warehouse, presenting the museum-quality collections of Howard Rachofsky and Vernon Faulconer to the public, was featuring works such as an impressive Cell by Louise Bourgeois or an uncanny puppet by Maurizio Cattelan, chanting the pace of the rushed public that is the one in-town-for-the-fair kind of one. There, my friend Stefan was participating in a sensationalist panel featuring Hauser and Wirth’s partner Paul Schimmel and Sotheby’s head Amy Cappellazzo, moderated by Sarah Thornton, author of the masterpiece 7 days in the art world. The political incorrectness of this conversation, where all notions of good and evil were twisted to make the market appear as the Invisible Heroic Force behind all celebration of (waspy, straight, and male) artistic genius was simply embarrassing for everyone. In Texas, land of contrast, the emperor’s clothes seem to be more transparent than ever.

John Dilg

Terence Gower

TR Ericsson

Yamini Nayar

Anthony Sonnenberg

Ida Ekblad

Trevor Shimizu

Jeff Ferrell

Irving Penn

Rachel Harrison

Mai Thu Perret

See this article in its original format on Terremoto HERE.