*to read this article on the American Craft Magazine website please click HERE

What Lies Beneath

Jessica Calderwood’s work invites viewers to dive deeper.

Published on Monday, March 18, 2019. This article appears in the February/March 2019 issue of American Craft Magazine.

Mediums Mixed Media Author Joyce Lovelace

How much of our true selves do we show to the world? When we look at others, do we see who they really are? Can we ever know what lies beneath the surface?

In her enameled paintings and jewelry, Jessica Calderwood captures imaginary characters in private moments and intimate places, with unguarded gestures: face in hands, fingers in mouth, belly button in extreme close-up. Surreal and enigmatic, her portraits have humor, attitude, and charm, but they’re also unsettling, for what they reveal and what they don’t.

Her long-standing Florals series shows female figures in soft pastels, demure dresses, strands of pearls. They’re lovely and ladylike in the old-fashioned sense, yet incomplete. In place of heads, they sport absurd botanical bursts – a bouquet of blooms, a puff of dandelion seeds, an artichoke. These human-plant hybrids are frozen in gestures of doubt and quiet despair. Even when they come in twos, as twins or mirrored, they’re essentially alone, personalities negated, in spaces devoid of outside influence. That these images are created in layers – rendered in powdered-glass paint on a shimmery metal substrate, fired dozens of times to develop complexity – adds to their dreamlike depth.

“I want to draw viewers in,” Calderwood says. “I want them to be attracted to the color and the surface. Then, I hope, they’ll start to wonder: ‘What’s going on underneath there? Literally and figuratively, what’s that about?’ ”

Gender, identity, and the body are themes Calderwood, 40, has mined in her art for two decades now, in personal, autobiographical ways. When she put her career as an artist and teacher on hold after the birth of her first child, she sensed a difference in the way people perceived her. “All of a sudden, I wasn’t anybody but ‘Mom,’ and it felt isolating,” she recalls. “I had to somehow address it.” On summer visits to her Moroccan-born husband’s family home in Rabat, she spent hours sketching plants and flowers in her mother-in-law’s lush Mediterranean garden. “I had pages of studies from years of trips. It marinated for a long time, until I realized the symbolism of the floral and the feminine,” and a rich body of work was born. Later, she would expand on the motif of concealment and censorship by portraying her subjects’ faces behind drapes.

“[Calderwood’s] ability to discern strangeness in the commonplace, the truth hidden behind a layer of artifice, lends her work its mystery and its power,” art historians Bernard Jazzar and Harold Nelson wrote in their book Little Dreams in Glass and Metal: Enameling in America, 1920 to the Present. The two first saw her work in a student show in 2002. “It stood out, both for its inventiveness and for its audacious subject,” they recall today. “We sensed immediately that Jessica represented a fresh new voice in the field, and we were intrigued.”

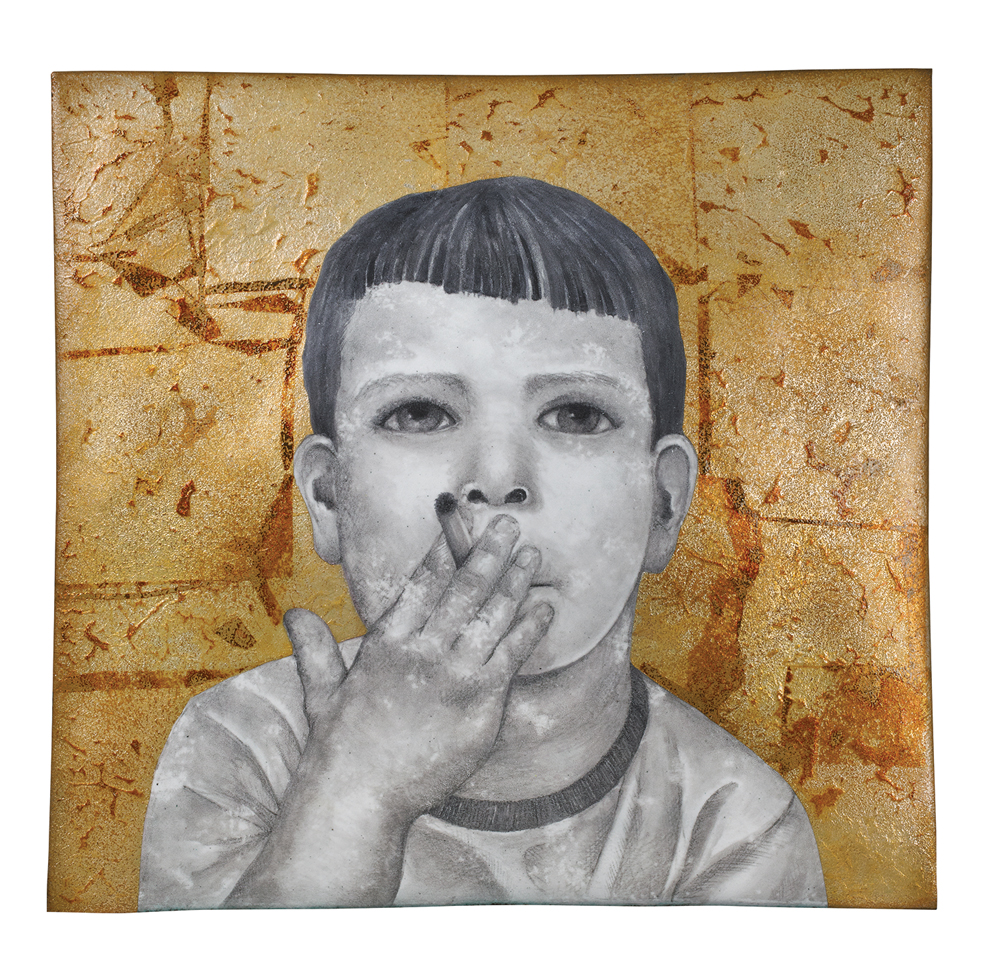

Jazzar and Nelson went on to purchase a number of her pieces (since donated to the collection of the Enamel Arts Foundation), the first being the startling 2005 wall panel Smoking Boy, in which a jaded-looking youngster takes a deep drag on a cigarette. Part of an early series on the subject of consumption, the image was inspired by a YouTube video of a Romanian child who was, she says, “smoking like a champ. The skill of his gesture was just so mature and disturbing.” With gold-colored foil inlaid in the background, the portrait resembles an early Byzantine mosaic, hinting at the almost religious nature of overindulgence in today’s culture. As Calderwood says, “I’m always trying to create tension between contemporary imagery and ancient process.”

It’s fitting that she hails from Cleveland, Ohio, for decades the center of enamel art in the United States. That distinction is largely thanks to the legacy of Kenneth F. Bates, the so-called dean of American enamelists, who taught at the Cleveland Institute of Art from the 1920s to the ’70s. Soon after Calderwood enrolled in 1996 as a painting major, she took an elective class in enameling; she changed her major the next semester.

“Once in the department, she was totally self-driven,” remembers her professor and mentor Gretchen Goss. “The moment I started working in that material, everything clicked,” Calderwood says. “I could have color and direct drawing and mark-making but also this other element of craft and process. I loved learning about firing with torches and kilns and soldering, just ate all of that up.”

She began exhibiting her work as an undergrad, then earned her MFA in metalsmithing at Arizona State University. Her work made the cover of Metalsmith magazine her first year in grad school, boosting her career as she steadily made a name for herself in the various worlds of enameling, jewelry, and fine art while experimenting with material and scale. In 2002 and 2014, she was an artist-in-residence at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center arts/industry program in Wisconsin, where she was able to re-create her figures as life-size cast-porcelain sculptures. In 2016, she became the head of metals and jewelry at Ball State University in Indiana.

Today, in her newly built backyard studio – “my dream forever,” she says – Calderwood alternates between enameled wall panels and jewelry (almost always brooches, because they’re good miniature canvases and easy to wear), doll-like china floral figures, and the occasional large installation, often with elements of fiber, polymer clay, and found objects.

Her latest direction involves “images of people immersed in a device, blocking the face and eyes as a way to reject any real interaction or connection” – something Calderwood finds increasingly troubling as a parent and teacher. At the dentist recently, her two boys were given electronic game consoles to occupy them while she got her teeth done; she was struck by the sight of them “sitting squished next to each other with the Nintendos completely covering their faces.” At the university, she says, “I’ll walk into my classroom and there’ll be 17 people sitting at desks, not talking to each other. They’re all buried in their phones.”

In her art, she offers an allegory for our age of online personas and virtual reality, where it seems the more exposed and linked we are, the more we’re obscured and misunderstood. But it helps to see that not all of Calderwood’s figures are desolate. Sometimes she shows us a couple, secluded in a moment of tender, passionate, physical embrace – as if to suggest that maybe, in the end, the answer is love.

A solo exhibition of Jessica Calderwood’s wall and sculptural work will open at Tory Folliard Gallery in Milwaukee on June 7.