#To see the original article on the Zeuxis website, please click HERE

Organizing Sensation

An Interview with Paula Swaydan Grebel - Gwen Strahle - John Goodrich

by Franklin Einspruch

Paul Celan (trans. Katharine Washburn and Margret Guillemin):

you, never-to-be-counted:

by one null-

token

you are ahead of

them all.

When I started writing criticism in the 1990s, the question was still hanging in the air of what period of art we were in, Pluralism having grown stale as a category. In the years following it became clear that the sheer number of artists and the proliferation of styles was such that an enterprising critic or curator could make a case for just about anything as an ascendant movement. Every so often an excitable critic dubs someone the finest artist of his or her generation, in derisive imitation of the one critic who got away with that in 1945. It never sticks. It won’t do to plug some novel phenomenon into the historical position occupied by High Modernism. We live in a different time, one that demands a more receptive critical approach, a willingness to look at all anew.

And what times they are. While some critics, the perpetual victims of historicism, are on the lookout for how artists are responding to the pandemic or the political events of the last year, I’m increasingly interested in the opposite, the artists who are able to bear down and work in spite of the mayhem going on in the world. Thus it was my honor and pleasure to interview three intensely committed painters, John Goodrich, Paula Swaydan Grebel, and Gwen Strahle, all of whom bring their distinct energies to the subject of still life.

Franklin Einspruch: Are you sensitive, personally or aesthetically, to the turning of the year? What sentiments does it generate, either in regards to New Year in general or this one in particular? Does it affect your painting or how you think about it?

John Goodrich: This year the thought of a vaccine on the horizon is a big boost! But generally, seasons don't change my frame of mind, beyond the fact that cold weather means I won't be painting outside. I enjoy painting whatever nature presents at the moment.

Paula Swaydan Grebel: With the turning of the year, I notice that the sky is darker at night, and the sun lowers during the afternoon. There are a lot of greys and browns. I miss the songbirds and all the unusual insects. I am aware of the quiet. Winter is when I travel west to visit with family. This interrupts my studio time, shakes things up, which has some benefits. I take in new views, ideas, and experiences. I will sketch and paint on the road and while visiting family. The key importance is to take the time to draw and paint. Creating art allows me to transcend to a better place. I am uncomfortable when I am not painting.

I paint year-round and never have big plans as the year ends. The quiet winter months are a good time to contemplate the experiences of 2020. It is also time for me to have a conversation with my paintings and set new goals for 2021 to keep me focused. I hope next year it is safer for all to return to some normalcy.

Gwen Strahle: It's going to be hard not to look back on 2020, and be ready for 2021. I can't say that I think too much about the new year in relation to my painting. I am usually entering into teaching a Drawing Marathon in January, at the Rhode Island School of Design. After five weeks, I have spring semester off, so I am geared up to have an uninterrupted time in my studio. I'm more focused on that turn, rather than the turning of the year. I am not teaching it this year as all Winter-session classes will be remote, so as of today I have steady time in the studio through February.

FE: Conventions, in my opinion, often get a bad rap. I've seen a lot of press releases singing the praises of some artist for defying conventions or nursing an unconventional approach. This seems to reinforce the myth of the artist as a professional flaunter of mores, for which there are examples, but they strike me as beside the point of why one would disdain a convention - it may be limiting, but limits can be productive. You've chosen the conventions of still life and figurative painting in general. What is your relationship with conventions?

JG: I'd agree that the art world too much resembles the fashion world in that sheer demonstrations of unconventionality seem to get the most attention. You could say that the convention of a painting having rectangular limits is actually what makes it most interesting – a painter can use these limits to give a sense of scale and momentum to whatever happens within the rectangle. At least that's what I get out of great painting, whether abstract or representational.

GS: I consider the still life not a convention but a vehicle. The still life gives me a freedom, in painting. So, it’s actually the opposite of limiting.

PSG: I do not think about any relationships with conventions while painting. The decisions I make about the work are intuitive. With that said, to be honest, art history matters in who I am as a painter. From years of study and painting, I am sure that what I have learned has internalized. The elements must feel right, the space, unity, movement, repetition, scale and proportion. Then there are times I'll push these ideas, place the object dead centre, then see how I can balance the picture. Cezanne's play with space and scale intrigues me. Right now I am attempting to alter conventional colors to see where it leads me. So, without thinking about it, I both follow and defy conventions.

FE: A common theme I find among the three of you is an interest in taming complexity. You include objects like baskets, scalloped glass, and the like, and then fight your way towards some kind of unifying principle. None of you are painters of detail for its own sake, which is the obvious way to handle complexity. Rather, you're looking for underlying phenomena. Is that a fair assessment? If so, how does it play out in your work? If not, how would you characterize it instead?

Pieter Bruegel The Hunters in the Snow 1565 oil on panel 46 x 63¾ in.

PSG: "Taming complexity" - I like this characterization. Your assess-ment is fair, I do search for a simplified scheme. It is a constant battle for me because I love to paint all that detail. For my work, I found it takes a lot of drawings, color studies, and rethinking before I find a good design. Afterwards, after all this looking, the details emerge and are placed with a purpose. I also look to historical painters whose work is complex yet solid. One such lesson came from "Hunters in the Snow" by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. I was curious to find the substructure underneath all his details. So yes, the underlying concern of mine is that of a unifying foundation.

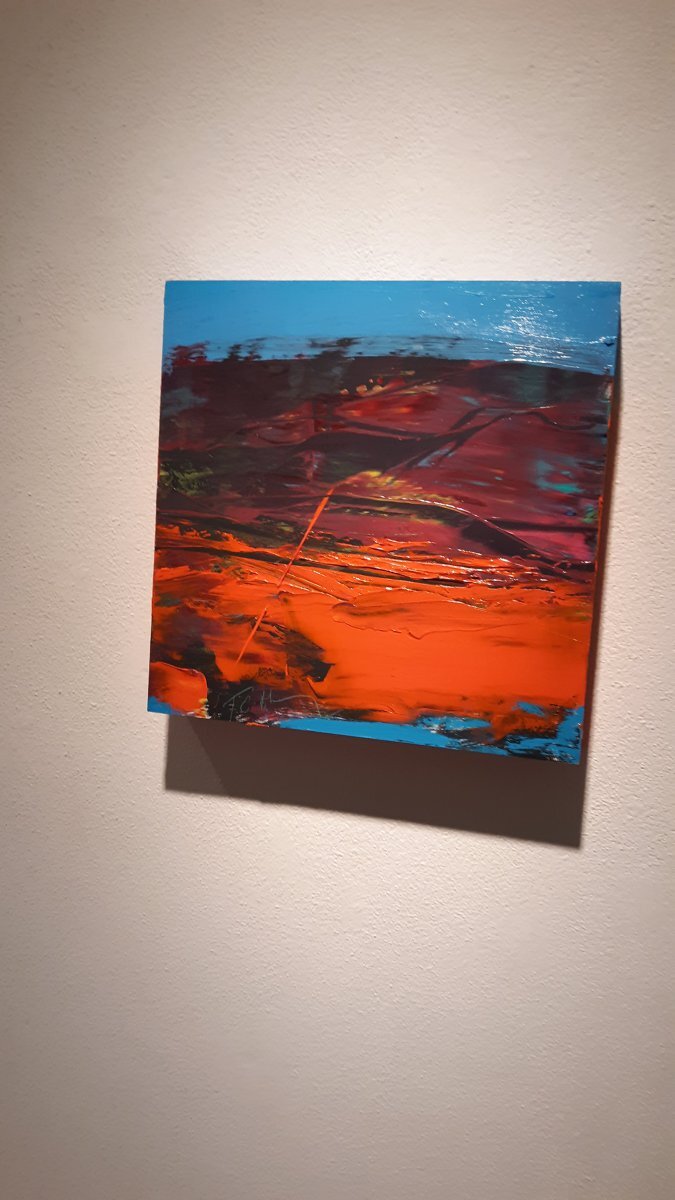

Paula Swaydan Grebel Bruegel Study, Hunter in the Snow 2019 oil on paper 12 x 16 in.

GS: That’s why I love the still life. It’s an arena. The still life is my painting world, and I can put objects in it, take them out, and move them around. One object may have a lead role in one painting, and then in the next painting, a supporting role. The search for “underlying phenomena”- that is absolutely a fair assessment. I see the still-life as a zone. A time zone, or a state of mind. It’s a slowing-down. The stillness is always amplified to me because I am painting from something still. Once I have a still-life world, an object has to be able to exist in it. The still-life world comes first, then the objects. What underlies isn’t usually about the literalness of the objects, though I like that I can paint about an object. What underlies is that painting world, which leads the way. I feel like this is a phenomenon.

JG: There's that great quote by Delacroix: "Exactitude is not truth". I tell my students that painting a scene realistically is not a matter of taking inventory, but of figuring out how each element counts uniquely with the painting. So for me the underlying phenomena is the visual energy of a scene, revealed by a particular light. Our perceptions are naturally subjective, and the task is to try to organize them pictorially, in the hope of uncovering the necessary character of each element. Sounds simple, but of course it's anything but!

FE: What role does the still life play in relation to the rest of your work?

GS: I’ve continuously been drawn to the intimacy of the still-life as a quiet, shallow space. But I have also seen the still-life as a landscape, a portrait, an abstract opportunity. I like that the still-life can be this metaphor for something else, and at the same time refer back to itself. Through painting the still-life, I have always felt a freedom. Just thinking about the phrase “still life” slows down time and allows me to contemplate stillness.

I love the objects that I choose to paint. Many I have painted for over forty years. I am interested in a painted world which will allow my objects to exist together in different ways. The particularities of their relationships can enhance and use their idiosyncrasies. Sometimes, I make a painting about a singular object. An object can have a different importance when alone in a painting; and I feel differently when I paint thinking only of one object. If a painting with one object hangs next to another painting with only one object, there might be a connection. Maybe the object wants to be in the other painting. If I am convinced, I may put these two objects together in my next painting.

PSG: The still life offers an excuse to paint indoors in the studio, away from distractions. It is not boring or expected. Each new day I approach the same setup with different emotions, attention, ideas. I may notice something that wasn't obvious to me before. It can be a hidden shape observed by grouping objects within their shadows. Unexpected colors appear when placed side by side with complimenting colors. The still life enables opportunities for long moments in looking. This allows discovery, surprises, and exciting occurrences. The still life offers endless perceptual moments and visual experiences that are exciting. It is another reason to make a painting, my favorite thing to do.

JG: I like considering a still life as an intimate version of a landscape, the difference being that you oversee the motif instead of occupying it, and you get a chance to re-arrange objects and maybe the light source. The still life is intimate and finite, and the landscape can be overarching and infinite, but for both one has to organize one's sensations.

JG: I'd put it this way: Our visual perceptions are subjective, which means that the way we compose a scene are too. The curve of a road might play a big part in locating other elements on the ground, or be just a faint echo of clouds in the sky. A tree's canopy might be a dense blotting out of sky, or an exuberant eruption from a trunk. Distant houses could be lively interruptions of the long drone of a horizon, or perhaps subtle echoes of foreground fence posts. The challenge is ordering everything at once, and this is so complex and intuitive a task that it may take many false starts and reworkings. Or, for me, countless abandoned efforts.

FE: John, could you say more about "organizing one's sensations"? What does that entail?

JG: I'd put it this way: Our visual perceptions are subjective, which means that the way we compose a scene are too. The curve of a road might play a big part in locating other elements on the ground, or be just a faint echo of clouds in the sky. A tree's canopy might be a dense blotting out of sky, or an exuberant eruption from a trunk. Distant houses could be lively interruptions of the long drone of a horizon, or perhaps subtle echoes of foreground fence posts. The challenge is ordering everything at once, and this is so complex and intuitive a task that it may take many false starts and reworkings. Or, for me, countless abandoned efforts.

FE: Paula and Gwen - do you have your own ways of organizing your sensations? To put it another way, what internal frame do you invoke in order to bring yourself to painting?

PSG: When I paint the still life, I respond to the depth of colors, shapes, design, and intrigue. The glass holes to look through, the stripes that peak over flat shapes, square versus round. My eyes enter the picture frame, I see the movement of things from here to there. I settle in one area, an area with more detail and brighter colors, harder lines. It is a play of all these that move the eye about. All is an excuse to make a painting, a design within the rectangle. If I am excited and can paint this beauty, then I am happy with the results. Another thing I have done is to make many small studies of the same set-up. I try different values and color combinations. This process has helped me to see what my options are. It helps me to edit, to better understand and express my point of view.

GS: I have a lot of objects in my studio. I have made paintings where I organize objects into a still-life. And, I have found still lifes made by accident. But because I work mostly from memory now, organization is a different, slower process, that seems fitting for the paintings I make. I am adding and subtracting much more than I ever have. I like that only I might know that an object once existed in a painting.

I believe when an artist walks into their studio, who they are as an artist reinforces their paintings and decision making. Of course there are other influences. I walk into my studio, and my paintings are there, with their problems that need to be solved. And that’s one way I get started. My own paintings influence me. When I am surrounded by my paintings, I am strengthened by who I am as a painter. That creates a natural organization of responsiveness, and a need to paint. For me, it is an intuitive and most important way of getting started. Also, I love paint. I love my objects. Somehow that combination has always been extremely important to how I end up making these paintings.

John Goodrich is a New York-based painter, teacher, and writer who exhibits at Bowery Gallery and with Zeuxis in New York City. His paintings have appeared in group shows at Elizabeth Harris Gallery, Kouros Gallery and Lori Bookstein Fine Art in New York City, the Contemporary Realist Gallery in San Francisco and numerous other venues around the country. His work has been mentioned in reviews in The New York Times, The New York Sun, The New York Observer, The New Haven Register and other publications.

Born in California, Paula Swaydan Grebel received her BFA in Figure Drawing and a Minor in Textiles from the California State University of Long Beach. After moving to Wisconsin in the 1990s she has continued studying here and abroad with key perceptual painters. Paula teaches painting and drawing workshops throughout the states. You will find her work in public and private collections worldwide. Paula's paintings have shown in group exhibitions in Italy and Berlin, Germany. Other shows include THERE an art space and First Street Gallery, New York. John Michael Kohler Art Center, and The Museum of Wisconsin Art, Wisconsin. The Foyer Gallery, Wichita, Kansas, Brick Gallery, Clarksdale, Mississippi, and Gallery HB, Huntington Beach, California. Represented by Tory Folliard Gallery

Gwen Strahle lives and works in eastern CT. She has been exhibiting with Zeuxis since 2012. Her work has been exhibited in galleries and museums across the country, and recently at Steven Harvey Fine Arts Projects. She holds a BA from Rhode Island College, and an MFA from Yale School of Art. She has been teaching drawing at Rhode Island School of Design since 1984, and has taught workshops at Art New England and Black Pond Studio.

While maintaining a studio practice as an artist in Boston, Franklin Einspruch is also active in art criticism, comics, and alternative publishing. His art has appeared in 19 solo exhibitions and 40 group exhibitions. He has been a resident artist at programs in Italy, Greece, Taiwan, and around the United States, and was the Fulbright-Q21/MuseumsQuartier Wien Artist-In-Residence for 2019. He has authored 221 essays and art reviews for many publications including The New Criterion and Art in America. He produces one of the longest-running blogs about visual art, Artblog.net, and a webcomic, The Moon Fell On Me. His imprint, New Modern Press, publishes the anthology Comics as Poetry and Cloud on a Mountain.